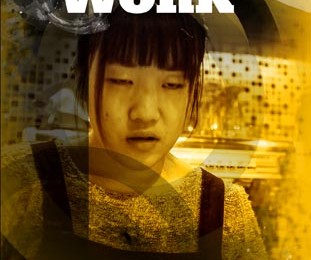

Work

Anti-Work: Realistic Resistance

‘I say to the wage class: Think clearly and act quickly, or you are lost. Strike not for a few cents more an hour, because the price of living will be raised faster still, but strike for all you earn, be content with nothing less.’

– Lucy Parsons, ‘The Principles Of Anarchism’.

‘An injury to one is an injury to all.’

– Motto of the IWW.

Most of us do not have the option to just drop out of the systems that exploit us because we have no other way to survive. Those who can move to a self-sufficient commune are few and far between, and while someone looking out for their own well-being can’t be looked on too poorly, in doing so they do not provide an example for the world (as it is often presented), but hide themselves from the struggles we face as a class.

The struggle against work is the struggle to have our needs met on our own terms. This puts us up against capitalism and the state. While individual battles can sometimes lead to small victories, these are isolated and any gains can be easily reversed at a later date. The strongest concessions won in the past have always happened when the working class has taken collective direct action.

Collective action means that we recognise that we have to work together as a group. Bosses may be able to sack one or two people and still keep their profit level steady, but it is often far simpler (and loses less profit) to concede to the demands of a large group or an entire workforce compared to getting into a lengthy fight with them. Direct action is where we try and solve a problem as directly as possible, without hoping that someone else will fix the problem for us.

Both in the workplace, on the dole, and in our neighbourhoods we can find unions presenting themselves as the place to go to solve our problems, by having members of the union bureaucracy sit in official negotiations with management. In order to have any say in these negotiations the union needs to be able to both start and stop any worker militancy. Therefore the interest of the union, and its paid bureaucrats, is not to do the best by workers but to become a layer of management with the main task of controlling our ability to take collective direct action. Union members who have an interest in fighting for the best are either isolated, given shop-floor roles that bury them under case work, or are convinced to fall in line. Although much importance is given to negotiations with the bosses, a union committee negotiating on our behalf rarely produces satisfactory results as they do not live with the same problems and have different interests to ourselves. In spite of these limitations, there can be good reasons to be part of your union. The local branch can be a place to meet workers who are itching to take militant action outside of the union’s restrictions and if it gives all members a fair vote in any decisions being made then it can produce effective results.

Before taking action we should undertake a realistic review of the situation and ask how much harm can we cause the target (given the number of people we can call upon and the energy they can put in), and how easy is it for them to give in. If the profits lost would be significantly more than the cost of conceding then the chances of winning are good. On the other hand if a boss has a lot to lose or can ignore any action being taken then the fight could be long and the chances of victory are slim.

One way to make our actions have more impact on the bosses is to work out a plan of escalation. This means that rather than throwing our most powerful punch from the start or simply trying out different actions in random order, we work out all the different methods of collective direct action we could take against the bosses and rate them from weakest to strongest (given how much we think they will hurt the boss and how much energy it will take out of those involved). We then start the campaign with the weakest action, and if it fails to work take the next on the list, working our way one step up the list each time an action fails to have the desired effect. This has some key benefits.

First, we might win concessions far sooner and for less effort than we believed would be possible, while people will not be tired out and lose heart when the first action is a big push that the boss manages to survive. We can use the space between each escalating step to prepare for any backlash from our actions, plan out the next stage, and even change course if required.

At the same time bosses don’t just have to weather the storm of our current activity but also have to start worrying about what we have planned for them next. The effects of profit loss happening now are compounded when there is a real fear of ever more profit-harming actions down the line, and it is often this factor that will win the struggle.

What follows is a brief introduction to some ways collective direct action has been used to win past struggles:

The Demand Delivery

This is usually the first action taken in a series of escalating tactics. A letter is produced with any outstanding grievances listed, the demands being made to resolve the issue, and a declaration that if they are not met within a certain time-frame then further action will be taken. The people with the grievances then gather along with as many people that will stand in solidarity with them and march on the target to deliver the letter. Once those with the grievance hand it over everyone leaves to clapping from everyone present before dispersing. While the action can be over in mere minutes the show of collective strength and support can sometimes be enough to sway the bosses’ mind.

Communications Blockade

Businesses today rely on their ability to stay in contact with customers, a state of affairs that can be exploited to our advantage. A communications blockade is where a mass of people complain about the situation at hand by phone, email, website, social media, and fax to the bosses all in the same time period. The length of time the blockage is set to take place in can be scaled to suit the numbers you have at your disposal, and it is a good action to engage friends, family and general supporters. Many smaller disputes have been won with a communications blockade. These tactics can also be adapted to targets that are particularly reliant on getting good reviews online.

Go Slows, Sit-Ins & Occupations

A go slow works exactly as it sounds. The workforce as a whole pick a speed to work at and stick to it rigidly. This is where collective action is vital as even if a few workers were to break from the agreed pace then there would be the chance to victimise those who refused to scab. Sit-Ins are similar to go slows only with a clear physical expression – people stop work and sit down. While this can be effective, management will carry on as best they can before security or police remove everyone. Occupations take this a step further and actually take over a plant and deny access to the management. The latter needs a high level of militancy and solidarity, as well as good rank-and-file organisation.

An occupation requires a high level of militancy and organisation on the part of the workers concerned. It is doomed if they remain isolated from the rest of organised labour and the working class generally but in the right conditions it can be dynamite. What is needed is mass involvement. Workers should not be presented with a plan: an effective occupation must be preceded by mass meetings to plan the occupation, and lots of promotion to gather popular support both in the place of work and beyond.

Occupation can also be used to prevent eviction by bailiffs, as groups of people use their own bodies to block the streets and entranceways to target properties. In areas where there are multiple houses under threat, a phone tree and internet call-outs can be used to gather people quickly, however nothing beats being at a property before the bailiff starts their work and staying until after they have gone home.

Boycott, Protest, Picket Line & Strike

Boycotts and protests try to hit the profitability of a business by pointing out the flaws of the employer and encouraging customers to shop elsewhere. Boycotts are rarely effective by themselves as they attempt to have the battle at the point of purchase, making it relatively easy for bosses to weather the storm and wait for customers to return.

Far more effective is to strike at the point of production. This involves the workforce and their supporters blockading the entrances, forming what is known as a picket line, and preventing scab workers from going in and the transport of goods or work vehicles from getting out. Wildcat strikes are when a workforce ballot in person and walk off the job there and then to form a picket. As this happens without notice the bosses ability to minimise the impact of a strike is non-existent.

Strike action can also be taken at the same time as other workplaces and communities even if you have no demands of your own. Even if the strikers are superficially unconnected, the act of solidarity striking makes the original demand easier to achieve as the bosses not only have to manage their own workforce but multiple strands of the economy being shut down. It is also in our own interests to make solidarity striking commonplace, as when it comes time for us to make a demand we know we can rely upon the mutual aid of others in achieving our goals.

Wildcat and solidarity strikes may be illegal, but combined they are the most powerful form of industrial action. When undertaken successfully they almost always included a demand to have no negative outcomes for the strikers which is backed by a threat of harsh repercussions if not kept.

Outside of the formal workplace there is also a history of reproductive labour strikes. This can take many forms, from a rent strike (where a group of tenants refuse to hand over rent until demands are met), through to sex strikes (organised by groups of women who refused sex with their partners unless conditions were changed for them). Any type of unpaid labour could be targeted and very quickly have a knock-on effect to be addressed.

The Sick In

A sick-in is a way to strike without striking. The idea is to cripple your workplace by having all or most of the workforce call in sick on the same day(s). Unlike a formal walk-out, it can be used effectively by departments and work areas instead of the whole workplace, and because it’s usually informal it can catch management unawares. Sometimes just the hint of ‘flu doing the rounds’ and the likelihood of it spreading to important areas of work can work wonders with a stubborn boss or supervisor.

Work to Rule

This is another powerful tool at our disposal today. Every industry is covered by a mass of rules, regulations and agreed working practices that, if applied strictly, can make work difficult if not impossible. While following the letter of the rules may inconvenience workers for a time, if they stay focussed it will ruin the profitability of a workplace and leave the boss powerless to fight back; after all, the workers are following the rules. Even an agreement not to take overtime for a short period can be effective if applied at the right moment.

Sabotage, Collective Theft and Expropriation

Another way that workers can choose to strike at the point of production is to put a spanner in the works. Machinery is damaged, parts go missing, work bottlenecks around vulnerable points in production, and all the workers say they have no idea what is happening. Other times, rather than things randomly breaking down, they just go missing. Businesses put in place all kinds of checks that keep a watch on the small scale, but they are rarely prepared for a large-scale theft that can’t be pinned on any one person. These are risky tactics, but sometimes needed.

This concept of collective theft can be used to have our social reproductive needs met while minimising the amount of paid work we have to do. Individualised shoplifting can be scaled up so a group enters the target shop together, sticks tight while loading up on goods, leaves quickly, and has a plan worked out in advance for how items will be redistributed to those that need them. Often this can be done while getting the passive support of staff.

This is known as expropriation, and as well as being done to items in a supermarket could also be applied to taking over property (such as when squatting an unused building), or when a point of production is taken into collective control.

Good Work & Taking Charge

Sometimes breaking the rules can hurt other segments of the working class in a way that turns them against your struggle, isolating you and giving the bosses a chance to win. Good work is coming up with ways to break the rules in a way that hurts the bosses but helps others. Letting customers go without paying, adding on extras, going the extra mile when you don’t have to, or bending the rules to make a job more fulfilling and satisfying to everyone except the bosses and their profits.

Taking charge takes good work and mixes in the ideas of an occupation, except here the workers agree as a group how to run their work and do it that way in the bosses face. When workers decide that they are going to do what they want to do, instead of what the employers want, there is not a lot can be done to stop it.

These act of collectively deciding how to subvert their job roles can bring workers closer to activity as it would be under communism, meeting people’s needs in a way that we can all find acceptable.

Social Media