What the Suffragettes did for us (hint: it was more than the vote)

Today marks the one hundredth anniversary of the Representation of the People Act receiving royal ascent. It was the state finally accepting that women were as capable of making decisions as men. Well, nearly, women still had to be nine years older in order to vote at the time.

It has meant that a lot has been written, said and broadcast about the Suffragettes this week. Some of it great, much of it either a little lazy or deliberately misleading. There’s been a notable upturn in media reporting on the more militant tactics the women used in their campaigning than in the past, so it’s certainly an improvement. As our contribution we’re republishing an article from Organise 84, written on the eve of a general election and with the Suffragettes firmly in mind.

Nearly all children in the UK are told at some point, by some well-meaning adult: “You must eat all the food on your plate, because there are children starving in Africa.” Around half of us are subjected to a second, similarly inane cliché. This one goes: “When you grow up, you must vote in every election, because women died to get you the vote.”

The connection, you might have noticed, is that they’re both wrong-headed appeals to a sense of moral duty towards somebody who will be entirely unaffected by the action we’re told we must take. They’re also massive over-simplifications of complex issues. They concern problems that are created by a vast, tangled network of systems of power, and promote solutions that look, on the surface, like a personal response to those systems, but which don’t question or disrupt them in any way.

Most of us are soon able to point out that starving children in specific regions within Africa or anywhere else are unlikely to know or care whether we finished our second scoop of over-salted instant mashed potato, though they might appreciate fairer global economic systems governing food production and distribution1.

It took me a lot longer to untangle the second fallacy. It was a lot longer before it occurred to me to try. In fact, there are several fallacies underlying this one, and it’s worth going through them in detail.

Fallacy no. 1: The Suffragettes would have cared about whether or not I vote.

Similar to the starving children in Africa, the suffragettes didn’t know me and had pressing problems of their own. What they wanted was not that every woman in perpetuity should be guilt-tripped into participating in any political system that used the ballot box to legitimise itself, but that wherever men were balloted, women would be too. As far as that goes, they got what they wanted, and those future women’s decisions on how to use that enfranchisement weren’t a major concern. In fact, the whole point was that they trusted future women to make their own decisions. Sylvia Pankhurst, for one, lived to reject parliamentary democracy as an out of date machine band refused to cast a vote or stand for election herself. I daresay that should she be haunting polling stations on May

7th, she would be far more appalled by the cuts to essential women’s services that every option on the ballot would continue to implement, than at women who spoiled their ballots or stayed away. I like to think she’ll give me an approving nod as I substitute my ballot paper for a sheet of folded bog roll, but honestly, if I believed in an afterlife I’d be sure that Sylvia Pankhurst, of all people, would be doing something better with it than haunting polling booths. She’s probably swanning round Europe with the spectre of communism.

Fallacy no. 2: The vote was the sole legacy of the suffragettes, and using it the only way to respect their memory.

Here’s the thing: the suffragettes never intended it to stop with the vote. They weren’t satisfied, and they didn’t intend us to be. We respect their memory by continuing their work, not by being content with it. We also need to remember that “suffragettes” was a blanket term for a diverse women’s movement.

The vote might have been the only demand of the more privileged groups, especially those in the US who refused membership to black, working class and

‘fallen women’ and were happy for the vote to be extended only to a married and propertied respectable few, but who’d want to honour their memory? For the Women’s Social and Political Union in the UK, at least at the beginning, there was a lot more to it than the vote itself.

Being denied the vote was an infantilisation, an insult to women as intelligent, rational human beings, regardless of how much use the vote itself would or wouldn’t be. Using the vote was almost beside the point compared to what it would mean for women to have the vote, to not be designated as mere extensions of their husbands but decision-making adults in their own right.

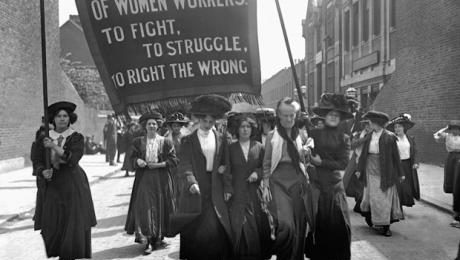

Getting the vote was a victory largely because of what women achieved through the process of fighting for it. The speeches, the publications, the meetings, the direct actions, the smashed windows, the battles with police, the martial arts training in preparation for those battles, the imprisonments, the hunger strikes, the resistance to force-feeding and refusal to give in: these did more to raise the status and confidence of women, the possibilities and opportunities for women as public, professional and political people, than the vote itself ever has, and a

shed load more than a woman Prime Minister and all the other careerists who’ve cynically used women’s struggles to promote themselves while throwing working class women under the bus.

Fallacy no. 3: Gratitude for the end of their disenfranchisement should put a particular obligation on women to involve themselves in the system that kept them disenfranchised.

“Do you see what mummy gave you? Now, say thank you very nicely, and stop complaining.” Because, frankly, fuck that condescending, paternalistic shit right there. Working class men also fought for the right to vote, but do they get that cooed at them every time they suggest that there are more effective means of change than the ballot box? This attitude turns women’s votes into an issue of conformity rather than conscience, in direct opposition to who the suffragettes were and what they fought for.

It was about women’s solidarity, women’s ability to work together and stand up and fight together, to write and speak from their own experience to each other and to the world, not just on the vote but sexual, social and vocational freedoms, including fair pay and reproductive rights.

The partial information we get fed at school paints the suffragettes as a peaceful campaigning lobby, who were awarded the vote because they made their case well and proved their economic worth while the men were being fed into the slaughter of the first world war. The truth is, the suffragettes achieved their aims because they were a radical, inspirational and effective direct action movement. They achieved incredible things for themselves and for future generations of women, and yes, they deserve our respect and our gratitude. But more than that, they deserve our study and our effort to comprehend the full enormity and complexity of their struggle. They deserve better than to be reduced to a single-issue soundbyte, their courage and militancy twisted into a liberal message of support for the system many of them never stopped fighting when their leaders were co-opted. They deserve so much better than to be used manipulatively, as bogey-women to shame us into a tokenistic legitimisation of the very systems they opposed.

So this polling day, whether you vote or organise or both, consider honouring the suffragettes’ memory by not using them as a stick to beat women with when they treat their vote exactly as the suffragettes fought to allow them to: as their own, to use or not, on their own terms.

1 Well, eventually. Most of us start by suggesting a parcel of leftovers

Social Media